Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is now by far the most common liver disease, even exceeding all forms of viral hepatitis, combined.

NASH is also quickly becoming the most frequent etiology of liver cirrhosis.

Despite this, NASH is still a widely unrecognized disease, not only by patients but also by physicians. All physicians should be aware that many of their patients may have undiagnosed NASH (ICD-10 code K75.81), which may have even progressed to NASH cirrhosis.

The liver inflammation of NASH remains asymptomatic for many years. Many patients learn of their disease only when it has already advanced to the cirrhotic stage.

The steatohepatitis of NASH is a consequence of accumulation of fat in the liver – mostly fatty acids but also cholesterol. These fatty acids, transported through the bloodstream as triglycerides, become toxic to the liver and trigger a chronic inflammation. The reason why is not yet clearly understood.

The accumulation of fat in the liver is not “normal.” The storage of fat is not a physiologic function of the liver. In NASH, the adipocytes are overwhelmed, and the excess fat distributes to the liver, a phenomenon that creates steatosis or fatty liver disease. With time, steatosis may lead to NASH and, ultimately, to liver cirrhosis.

NASH cirrhosis is the end stage of NASH, and NASH itself is fast becoming the most frequent etiology of liver cirrhosis. If a patient has NASH or is suspected of having NASH, concern about cirrhosis can be raised by the consistency of the liver at palpation. A healthy liver is soft; a cirrhotic liver will feel hard to the touch.

Two simple tests can also be supportive of a NASH cirrhosis diagnosis:

The design of the NAVIGATE Study, “A Seamless, Adaptive, Phase 2b/3, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Multicenter, International Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Belapectin (GR MD-02) for the Prevention of Esophageal Varices in NASH Cirrhosis” (NCT04365868), reflects the unmet medical needs of NASH patients with compensated cirrhosis who have not yet developed esophageal varices. The trial is sponsored by Galectin Therapeutics Inc., the leading developer of therapeutics that target galectin proteins.

This seamless, adaptive, two-stage, Phase 2b/3, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-groups, placebo-controlled study will assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the belapectin, a galectin-3 inhibitor, compared with placebo in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) cirrhosis and clinical signs of portal hypertension but without esophageal varices at baseline.

Unlike most other clinical trials focused primarily on earlier stages of NASH, the NAVIGATE Study population comprises patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Based on the results of earlier Phase 2 trials (Gastroenterology S0016-5085(19)41895-7. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.296), the NAVIGATE Study is focused on NASH cirrhosis patients who have not yet developed esophageal varices but are at increased risk of developing these potentially life-threatening complications.

The study will enroll approximately 315 NASH patients in the Phase 2b part of the trial at approximately 130 sites in 12 countries in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia. See here for a full list of currently active trial sites.

During the Phase 2b part of the trial, two belapectin doses, 2 mg/kg of lean body mass (LBM) and 4 mg/kg LBM, will be compared to placebo. Prior trials have demonstrated the good tolerance profile and apparent safety of belapectin with doses of up to 8 mg/kg LBM, notably for up to 52 weeks of treatment in patients with NASH cirrhosis.

The study design provides for a prespecified interim analysis (IA) of efficacy and safety data conducted after all planned subjects in the Phase 2b component have completed at least 78 weeks (18 months) of treatment and a gastro-esophageal endoscopic assessment.

The trial’s adaptive design allows patients to seamlessly transition from the Phase 2b component into the Phase 3 stage, as well as helps determine the optimal dose, bolsters the efficacy signal, and re-evaluates the sample size and statistical power for the Phase 3 stage of the trial.

The NAVIGATE Study was purposefully designed to make it easier for both patients and their caregivers by aligning closely to the Standard of Care for NASH cirrhosis patients.

For patients with compensated cirrhosis and PH without varices, there are no specific therapies indicated for reducing PH or directly treating the underlying liver disease.

Bleeding varices are a cause of death in about one-third of cirrhotic patients. There is no approved treatment for preventing varices in these patients. While beta-blockers are efficacious in improving outcomes in patients with portal hypertension and varices, they likely do not prevent development of varices or slow disease progression in early stage cirrhosis patients. As a result, clinical guidelines in the U.S. and E.U. do not recommend the use of beta-blockers for the prevention of variceal formation.

The development of new varices reflects the progression of hepatic cirrhosis and thus portends the development of other cirrhosis complications and outcomes, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and liver failure.

The progression of cirrhosis, regardless of etiology, is often defined by clinical outcomes. In particular, cirrhosis can be said to have compensated and decompensated stages, both with different features, prognoses, and predictors of death.

In compensated cirrhosis, patients have yet to experience the more serious symptoms of NASH cirrhosis; indeed, they may appear asymptomatic.

Decompensated cirrhosis, on the other hand, is characterized by the development of clinical complications of portal hypertension, such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, or liver failure. The more severe stage of decompensated cirrhosis is defined by the development of recurrent variceal hemorrhage, refractory ascites, hyponatremia, and hepatorenal syndrome.

One study found that patients with compensated cirrhosis had an expected one-year mortality rate of 5.4%. In decompensated cirrhosis, the one-year mortality was around 20%. Compensated patients with no esophageal varices had a longer survival than patients with varices.

The goal in treating NASH cirrhosis, therefore, is to maintain the patient in the compensated cirrhotic stage as long as possible or, potentially, reverse the cirrhotic process. The development of small esophageal varices is seen as clinical evidence that a patient is on the verge of decompensating.

The NAVIGATE Study is focused on preventing the development of esophageal varices in patients with compensated NASH cirrhosis. No varices means no potential for bleeding varices, a cause of death in a third of NASH cirrhosis patients.

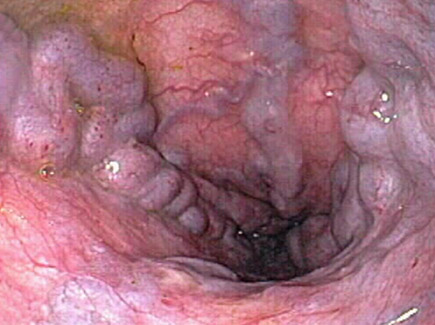

Small Varices

Medium Varices

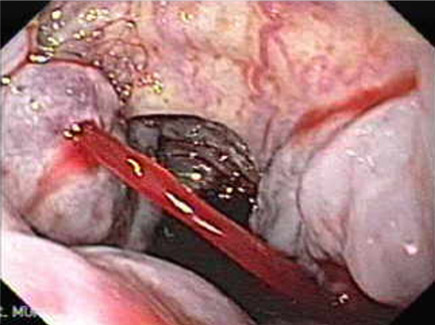

Bleeding Varices

The NAVIGATE Study has very specific criteria. In general, patients must:

A list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the NAVIGATE Study can be found at clinicaltrials.gov.

If you think that participation in the NAVIGATE Study is appropriate for your patient, contact one of the trial sites convenient to the patient to begin the initial screening.

See clinicaltrials.gov for a full list of currently active study sites and their contact information.

Study sites for the NAVIGATE Study are currently located throughout the U.S. Sites are also participating in Canada, Mexico, and the rest of the world.